BIP-327 MuSig2 in Four Applications: Inscription, Bitcoin Restaking, BitVM Co-sign, and Digital Asset Custody

This article introduces the applications of the BIP-327 MuSig2 multi-signature protocol in four of the most trending fields: Inscription, Restaking, BitVM Co-sign, and Digital Asset Custody.

Authors: Qin Wang (CSIRO), Cynic (Chakra), mutourend (Bitlayer) and lynndell (Bitlayer).

1. Introduction

Current Bitcoin transactions use the CheckMultiSig to validate n-of-n multi-signatures, which necessitates publishing a number of signatures and public keys proportional to the number of signers on the Bitcoin blockchain. This approach not only reveals the total number of transaction participants but also increases transaction fees with the number of signers. To address this issue, researchers proposed the Schnorr multi-signature protocol, MuSig, in 2018. However, this protocol required three rounds of communication among signers, resulting in a relatively poor user experience, which limited its widespread adoption and application.

In 2020, the introduction of MuSig2 marked significant progress in interactive signatures by reducing the three rounds of communication to two, thus offering a better user experience. Additionally, MuSig2 allows a group of users to jointly generate a single signature and public key to validate a transaction, enhancing privacy and significantly reducing transaction fees. After more than three years of continuous improvement, Schnorr multi-signature (MuSig2) has been implemented in wallets and devices.

Related proposals for MuSig2 include:

- 2022 Bitcoin BIP-327: MuSig2 for BIP340-compatible Multi-Signatures

- Recent updates on GitHub, now merged into the Bitcoin BIP library.

The Bitlayer and Chakra research teams have found that, with the growth of Inscription, Bitcoin Restaking, BitVM, and digital asset Custody, BIP-327 MuSig2 holds significant application potential. Theoretically, it supports an unlimited number of signers participating in transactions, saving on-chain space, reducing fees, and enhancing security, privacy, and operability.

Inscription: Inscription involves embedding customized content into Bitcoin’s satoshi units. This method has garnered significant attention due to its ability to create immutable and verifiable records directly on the blockchain. Inscriptions can range from simple text to complex data structures, providing a reliable way to authenticate the authenticity and provenance of digital assets. The permanence and security of blockchain inscriptions make them highly valuable for applications such as digital identity verification, proof of ownership, and timestamping of critical information. For inscriptions, MuSig2 can improve signing and verification speeds, reduce transaction fees during minting, and provide the necessary security for off-chain indexers, thereby enhancing the overall reliability of the inscription ecosystem.

Bitcoin Restaking: Bitcoin holders reallocate their staked assets to support various blockchain protocols or decentralized finance (DeFi) applications. This process allows Bitcoin to play multiple roles within the blockchain ecosystem, enhancing its utility and earning potential. By participating in restaking, users contribute to the security and functionality of other networks while maintaining their Bitcoin holdings. This innovative approach leverages Bitcoin’s liquidity and security, promoting a more integrated and efficient blockchain economy. However, Bitcoin lacks the contract capabilities needed for liquid staking, and the UTXO architecture is incompatible with the flexible withdrawal functionality of staked tokens. Therefore, MuSig2 is needed to enable liquid staking for Bitcoin.

BitVM: BitVM is a framework that implements smart contract functionality on the Bitcoin network. Unlike Ethereum’s Virtual Machine (EVM), which natively supports complex smart contracts, BitVM aims to extend Bitcoin’s scripting capabilities to facilitate more complex programmable transactions. This development opens new avenues for decentralized applications (dApps) and sophisticated financial applications on Bitcoin, overcoming the limitations of its simple scripting language. The introduction of BitVM represents a significant evolution in Bitcoin’s utility, bridging the gap between Bitcoin and other more flexible smart contract platforms. BitVM requires pre-signing to achieve a 1-of-n trust assumption and permissionless challenge functionality without needing a soft fork. To minimize the trust assumption, the value of n should be as large as possible. However, the existing CheckMultiSig script requires high transaction fees for verifying large-scale multi-signatures, making it impractical. MuSig2 can allow n to be as large as possible, making the value of n limited not by the Bitcoin block or stack size but by the actual number of cosigners that can be coordinated, with lower costs.

Digital Asset Custody: Digital asset custody involves using blockchain technology to securely store and manage digital assets, such as cryptocurrencies, NFTs (non-fungible tokens), and other tokenized assets. It includes protecting private keys, ensuring access control, and providing defense against network threats. Threshold signatures play a crucial role in the secure management of digital assets by enabling the distributed management of cryptographic keys. This technique divides a private key into multiple shares and distributes them among different participants. To sign a transaction or access digital assets, a predetermined threshold number of shares must be combined, ensuring no single party can control or misuse the assets unilaterally. This enhances security by mitigating the risks of key leakage, insider threats, and single points of failure. Additionally, threshold signatures offer a more robust and flexible governance model for digital asset management, allowing secure collaboration and decision-making in decentralized organizations and multi-party systems. Combining threshold signatures with MuSig2 can simultaneously meet the needs of Inscription, Bitcoin Restaking, BitVM co-sign, and digital asset custody, achieving an efficient multipurpose solution.

2. MuSig2 Principle and Implementation Specification

2.1 MuSig2 Principle

Initial: The group $\mathbb{G}$ has a generator $G$ and order $p$. Collision-resistant hash functions $\mathsf{H_{agg}}, \mathsf{H_{non}}, \mathsf{H_{sig}}$ map arbitrary length data $\{0,1\}^*$ to random integers in $\mathbb{Z}_p$.

KeyGen: There are $n$ signers. Each signer $i$ selects a random number $x_i \in \mathbb{Z}_p$ as their private key and computes the corresponding public key: \(X_i = x_i \cdot G.\)

PublicKeyAggregate: Let $L = {X_1, \ldots, X_n}$ be the set of public keys. Define $\mathsf{KeyAggCoef}(L, X_i) = \mathsf{H_{agg}}(L, X_i), $ then the aggregate public key $\tilde{X}$ is calculated \(\tilde{X}=\sum\limits_{i = 1}^n {(a_i\cdot X_i)}.\) Here, $a_i = \mathsf{KeyAggCoef}(L, X_i)$ is the aggregation coefficient.

Sign Round 1:

-

Commitment: Signer $i$ selects $\upsilon$ random numbers $r_{i,j} \in \mathbb{Z}_p$ for $j \in {1, \ldots, \upsilon}$, computes, and outputs $\upsilon$ commitments \(R_{i,j}:=r_{i,j}\cdot G, j\in\{1,...,\upsilon\}.\)

-

Commitment Aggregation: The aggregator receives the commitments $(R_{1,1}, \ldots, R_{1,\upsilon}), \ldots, (R_{n,1}, \ldots, R_{n,\upsilon})$ and sums them \(R_j=\sum\limits_{i = 1}^n {R_{i,j}} ,j\in\{1,...,\upsilon\}.\)

Sign Round 2:

- Signature: Signer $i$ inputs the aggregation coefficient $a_i$, aggregated commitments $(R_1, \ldots, R_\upsilon)$, aggregated public key $\tilde{X}$, and message $m$, and computes as follows:

- Signature Aggregation: The values $s_1, \ldots, s_n$ are summed \(s:=\sum\limits_{i=1}^{n}{s_i}\mod p.\) The aggregate signature is $(R, s)$.

Verification: The verifier inputs the message $m$, the aggregated public key $\tilde{X}$, and the signature $(R, s)$, and computes \(c:=\mathsf{H_{sig}}(\tilde{X},R,m).\) Then verify the following equality \(s\cdot G=R+c\cdot\tilde{X}.\)

The consistency is as follows: \(s\cdot G=(\sum\limits_{i=1}^{n}{s_i})\cdot G =\left(\sum\limits_{i=1}^{n}{\left(ca_ix_i+\sum\limits_{j=1}^{\upsilon}{(r_{i,j}b^{j-1})}\right)}\right)\cdot G =R+c\cdot\tilde{X}.\)

2.2 MuSig2 Implementation Specification

Recently, Bitcoin core contributor Andy Chow proposed several BIP proposals:

- BIP-328: Derivation Scheme for MuSig2 Aggregate Keys [Application Layer]: Describes how to construct BIP 32 extended public keys based on BIP 327 MuSig2 aggregate public keys, and how to use these BIP 32 extended public keys for key derivation.

- BIP-373: MuSig2 PSBT Fields [Application Layer]: Adds fields for random numbers, public keys, and partial signatures in BIP174 Partially Signed Bitcoin Transaction (PSBT).

- BIP-390: musig() Descriptor Key Expression [Application Layer]: Provides a method for transaction outputs controlled by MuSig2 wallets.

These steps are necessary for the adoption and integration of MuSig2 in wallets. These BIPs and specifications encompass all the requirements for integrating MuSig2 into wallets. Additionally, many wallet developers and collaborative custody solutions (see “Getting Taproot ready for multisig”) have long demanded standardization of the MuSig2 protocol. Now, with the formal BIPs in place, the community can independently review, provide feedback, and help raise awareness.

3. MuSig2 in Four Applications

3.1 Inscription

The most typical application of inscription is constructing BRC20, which can be viewed as an NFT token on Bitcoin. Its core design involves using the Ordinals protocol to inscribe data onto each satoshi, enabling simple operations. Generally, there are three steps involved.

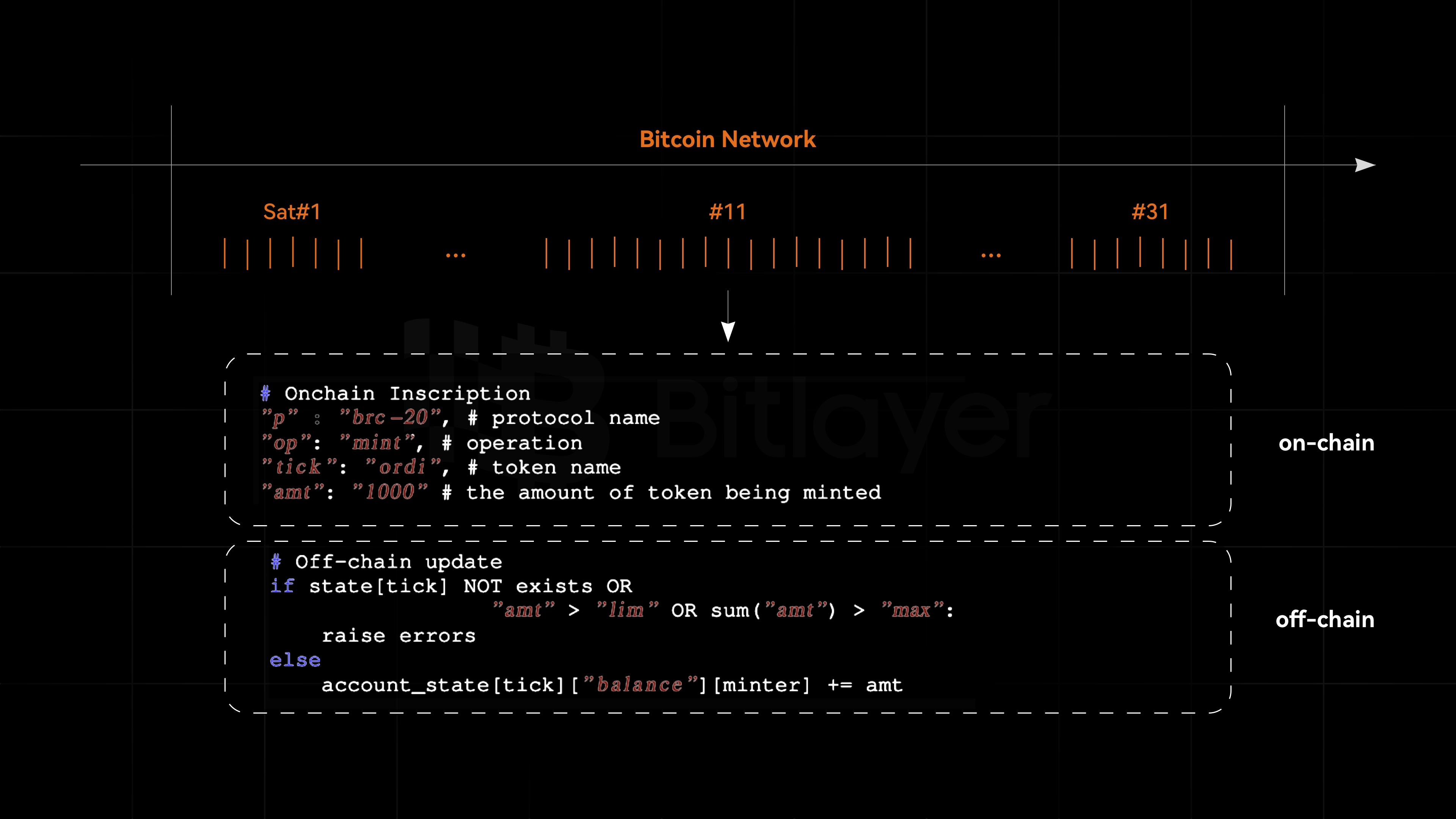

Step 1: Tracking the Uniqueness of Each Satoshi. Since satoshis are the smallest and indivisible units of Bitcoin, and the total supply of Bitcoin is 21 million, the upper limit of available satoshis is 2.1 quadrillion. Each satoshi in Bitcoin is unique, possessing individual uniqueness, which forms the underlying logic for establishing NFTs on Bitcoin. Each satoshi is assigned a sequential identifier (through the Ordinals protocol) and managed in a first-in, first-out manner to ensure precise tracking and orderly processing. As shown in the diagram, each satoshi is part of a complete sequential series, exemplified by satoshi #1, #11, and #31.

Step 2: Embedding Messages in Satoshis Using JSON Format and Taproot Script. Messages are stored in the SegWit field, ensuring an efficient and secure process. The script embeds the JSON in the satoshi, specifically within the OP field. The OP_IF starts the condition check, and the embedded content is placed after the OP_FALSE field, ensuring that the subsequent content is not executed but only stored. Thus, the embedded JSON is fully stored on the satoshi. Figure 1 shows the embedded JSON content, containing key parameters for deploying BRC20 tokens. It specifies the protocol as “brc-20,” the operation type as “deploy,” the token symbol as “ordi,” the maximum supply as 21 million, and the minting limit as 1,000. Key BIPs supporting this process include Schnorr Signature (BIP340), Taproot (BIP314), Tapscript (BIP342), and SegWit (BIP141).

Step 3: Identifying BRC20 Tokens Involves Off-Chain State Management by Indexers. These indexers parse and interpret the state of BRC20 tokens based on historical transactions. They analyze on-chain data, check token states, and update balances to ensure information is up-to-date. Additionally, lightweight clients integrate this information, enabling users to seamlessly identify and manage their BRC20 tokens.

For deployment and minting operations, only one transaction is needed, whereas transferring BRC20 tokens (i.e., transfer operation) requires two transactions. In the first transaction, there is a basic required on-chain inscription by the sender, similar to the minting operation. In the second transaction, another transaction completes the transfer from the sender to the receiver. The off-chain indexer then updates the state. If conditions are met, the indexer deducts the corresponding amount from the sender’s balance and credits it to the receiver’s balance.

We can observe that Schnorr signatures have been used in Bitcoin’s Taproot upgrade, enhancing the privacy and efficiency of Bitcoin transactions. The upgraded Schnorr multi-signature (MuSig2) can be seamlessly integrated into the Taproot upgrade, naturally aligning with inscriptions and the creation processes similar to BRC20. The new upgraded inscriptions can improve signing and verification speeds and further reduce transaction fees required during minting.

Another application pertains to the off-chain indexer part. The current indexers are essentially off-chain verifiers, with different service providers offering their own indexer update services. The associated risk arises from the lack of trust, similar to many sidechain and Rollup service providers, where users cannot trust relatively centralized service providers. Although these indexers do not store users’ funds, incorrect or delayed quotes can cause transaction failures for users. MuSig2 provides a multi-signature approach. It can introduce relatively decentralized and numerous verifiers to jointly maintain the same indexer, performing joint validation and signing at specific nodes, similar to a checkpoint mechanism. Users can at least trust that the indexer has honestly and reliably submitted on-chain inscriptions and transaction flows before the checkpoint. Thus, MuSig2 provides the necessary security for off-chain indexers, enhancing the overall reliability of the inscription ecosystem.

3.2 Bitcoin Restaking

Unlike PoS chains like Ethereum, which have native staking mechanisms, Bitcoin is maintained by a PoW consensus mechanism and requires additional mechanisms to implement staking functions. Currently, the most well-known proposal is Babylon’s Bitcoin staking scheme.

In the Babylon staking mechanism, users complete staking through a BTC staking script defined by Babylon, called a staking transaction, which produces a staking output. The staking output is a Taproot output with its internal key disabled by setting it to a NUMS point. There are three available script paths to implement the staking function:

- Time-lock path: Implements the locking function for staking.

- Unstaking path: Allows for early termination of staking.

- Forfeiture path: Implements the penalty function for malicious behavior.

The Bitcoin staking mechanism provides Bitcoin holders with a relatively secure interest-bearing solution, enhancing the utility of Bitcoin assets. However, this staking somewhat compromises Bitcoin’s liquidity. Nevertheless, the exploration of staking mechanisms on Ethereum over the years has paved the way for Bitcoin staking, where liquid staking can be used to address this issue.

Liquid Staking Introduces Custodians of Assets. Users deposit assets into the custodian address of a liquid staking project and receive a corresponding proportion of Liquid Staking Tokens (LST). The project stakes the collected assets natively, and LST holders automatically share in the staking rewards. Furthermore, LST holders can directly trade LST on the secondary market or burn LST to redeem the original staked assets.

Liquid staking on Ethereum can be implemented through smart contracts. However, Bitcoin lacks the contract capability required for liquid staking, and its UTXO architecture does not effectively support the withdrawal functionality for arbitrary denominations of LST. Currently, without the activation of contract opcodes like OP_CAT, there is no effective way to restrict the future spending methods of Bitcoin transaction outputs. Therefore, MuSig2 is needed to realize liquid staking for Bitcoin.

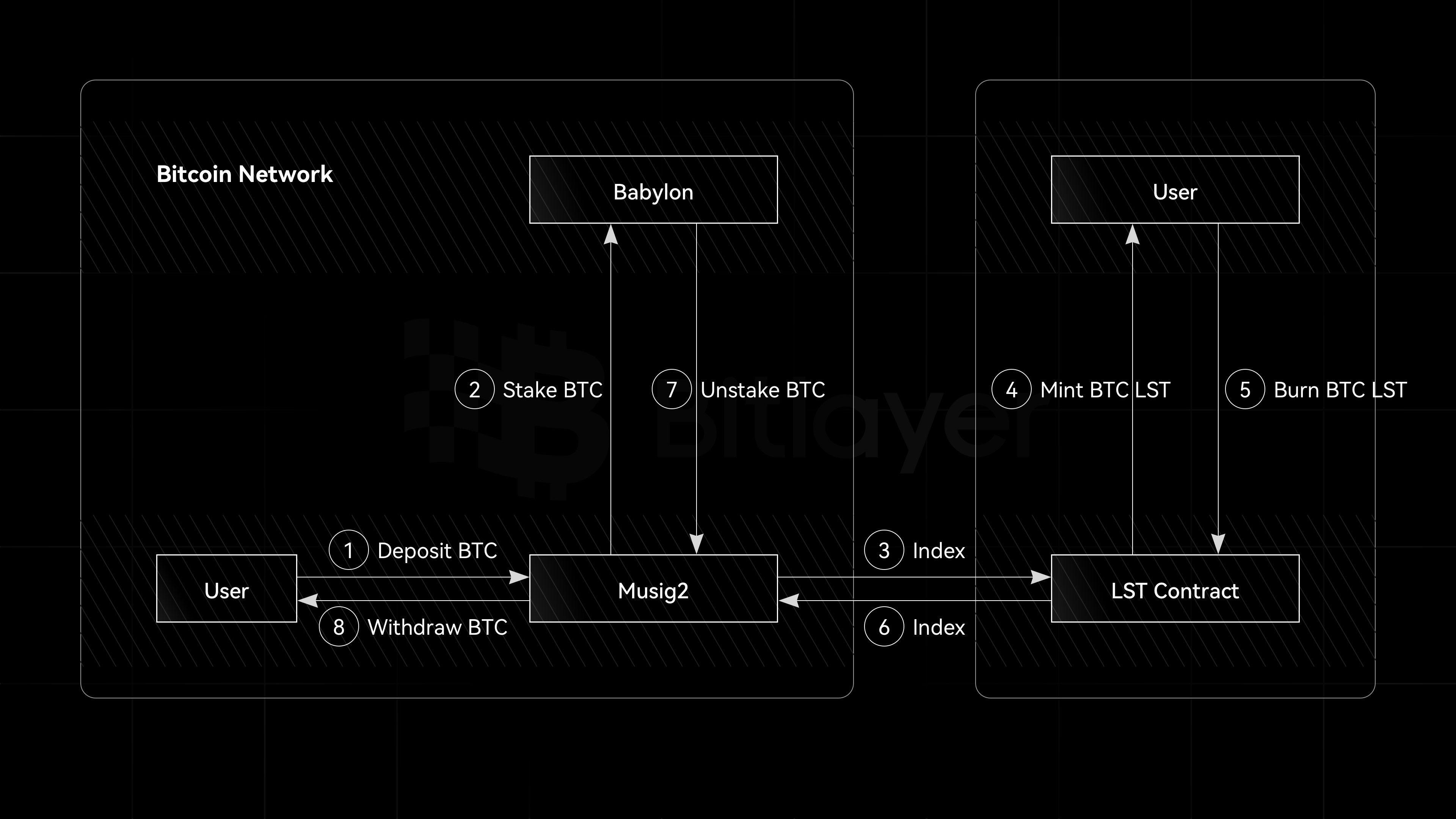

As shown in Figure 2, in Chakra liquid staking, users first transfer Bitcoin to a multi-signature address supported by MuSig2. This event is captured by the indexer, which calls the on-chain contract to mint ckrBTC for the user. The Bitcoin in the multi-signature address is staked into Babylon. While holding ckrBTC, users continue to earn rewards from Babylon staking. When users want to end the staking, they can burn ckrBTC. The indexer detects the burn event, performs the unstaking operation, and returns the Bitcoin to the user. Additionally, users can directly trade on the secondary market to exchange ckrBTC for Bitcoin.

Compared to self-custodial staking, MuSig2-supported liquid staking involves multiple participants maintaining the security of digital asset custody while also releasing the liquidity of staked Bitcoin, allowing LST to play a larger role in BTCFi and providing users with greater returns.

3.3 BitVM Cosign

In October 2023, Robin Linus published the BitVM: Compute Anything on Bitcoin white paper, implementing stateful Bitcoin scripts using Lamport one-time signatures. This system achieves Turing-complete Bitcoin contracts through an optimistic challenge mechanism without introducing new opcodes or soft forks. The system demonstrated the ability to verify arbitrary computations on Bitcoin using a NAND gate binary circuit constructed solely from OP_BOOLAND and OP_NOT opcodes. However, the compiled circuit size is enormous and impractical for real-world applications. Subsequently, BitVM1 used RISC-V instructions to express programs, fully leveraging all opcodes available in the Bitcoin system to improve efficiency.

BitVM2 expanded on BitVM1 in two ways: (1) In BitVM1, challengers were committee members involved in the initial setup, whereas, in BitVM2, challengers can be any participants. This eliminates the risk of collusion among committee members present in BitVM1, as BitVM2 challengers are permissionless. (2) BitVM1 required multiple rounds of challenges, resulting in long cycles, while BitVM2 takes advantage of the simplicity of ZK Proofs and the script expressiveness of Taptree, reducing the challenge cycle to only two rounds. This also decreases the number of pre-signed transactions required for peg-ins from around 100 to approximately 10. Specifically, BitVM1 used binary search to find the erroneously executed RISC-V instructions through multiple interactions, whereas BitVM2 verifies not the program itself but the correctness of its ZK proof execution. BitVM2 splits the ZK verification algorithm into multiple sub-functions, each corresponding to a Tapleaf. When challenged, the operator must reveal the values of each sub-function, and any inconsistencies can be punished by initiating a Disprove transaction.

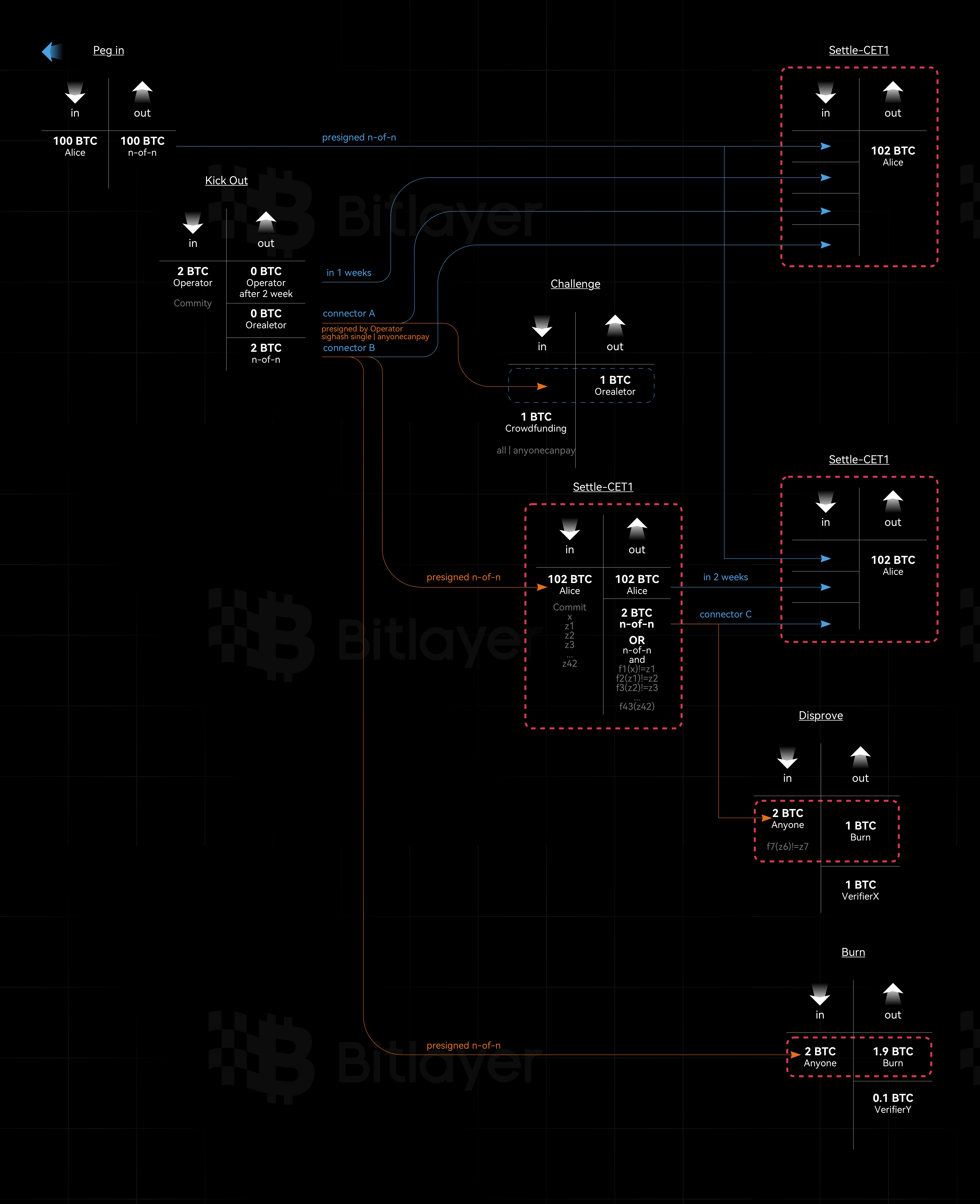

As shown in Figure 3, BitVM2 requires a large number of n-of-n pre-signatures. Since users do not know which Operator will front the funds for them, the BitVM committee must pre-sign five transactions—Take1, Take2, Assert, Disprove, and Burn—with an n-of-n signature before initiating the Peg-in transaction. Users will only deposit funds into the n-of-n multi-signature controlled address after confirming that all descendant transactions have been pre-signed. When users wish to withdraw funds, they can initiate a Peg-out transaction, with one Operator fronting the funds, thereby completing the withdrawal.

Operators need to stake 2 BTC to reimburse the fronted Bitcoin. If unchallenged, the Operator can successfully reimburse through the Take1 transaction. If the Operator acts maliciously, anyone can initiate a challenge by crowdfunding 1 BTC. In the event of a challenge, if the Operator does not respond, the Burn transaction is executed, destroying 1.9 BTC and giving the remaining 0.1 BTC to the address specified in the Burn transaction. If the Operator responds, the Assert transaction is executed. There are two scenarios:

- Case 1: If there is an inconsistency in the revealed sub-function values, anyone can initiate the Disprove transaction, destroying 1 BTC and giving 1 BTC to the address specified in the Disprove transaction.

- Case 2: If the sub-function values are consistent, the Operator can successfully reimburse through the Take2 transaction after two weeks.

In the BitVM2 system, the BitVM committee must pre-sign the Take1, Take2, Assert, Disprove, and Burn transactions with an n-of-n signature. The trust assumption for BitVM is 1-of-n, where a larger n value lowers the trust assumption. However, such large-scale multi-signature setups incur extremely high transaction fees, making them nearly impractical on Bitcoin. MuSig2 can aggregate a large number of multi-signatures into a single signature, minimizing transaction fees and theoretically supporting an infinitely large n value, depending on the actual number of coordinated cosigners, such as n values of 1000 or even larger.

When deploying BitVM, to prevent the BitVM committee from colluding to spend funds via n-of-n multi-signatures, at least one cosigner is required to delete their private key after the Peg-in setup. This ensures that funds in the BitVM bridge can only be spent through the honest front payment of the Operator, using reimbursement transactions. This improves the security of the BitVM bridge.

3.4 Digital Asset Custody

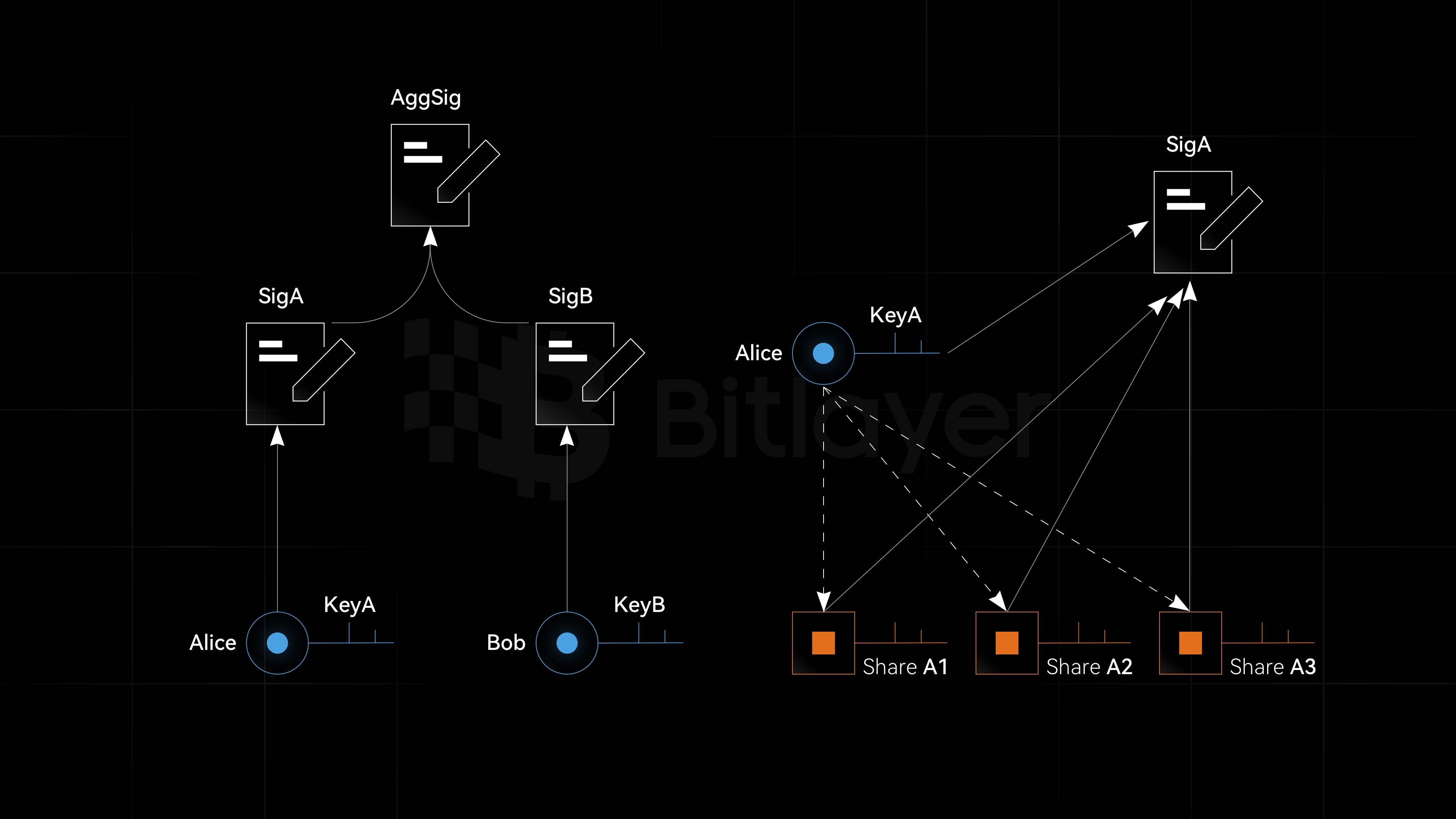

Aggregate signatures allow multiple signatures to be combined into a single signature, simplifying the verification process and improving efficiency. As shown in Figure 4, Alice generates signature SigA using her complete private key KeyA, and Bob generates complete signature SigB using his complete private key KeyB. SigA and SigB are then aggregated to produce the aggregate signature AggSig. This method ensures the independence and responsibility of each participant while enhancing the overall system’s security, as both parties must participate in any authorization operation. Through this collaboration, Alice and Bob achieve more secure and efficient digital asset management, preventing single points of failure and malicious actions, while also simplifying the complexity and cost of transaction verification.

On the other hand, Alice uses threshold signatures, generating and managing digital signatures with distributed devices, ensuring that no single device possesses complete signing capability. Specifically, the threshold signature scheme splits the private key into several shares, with each device storing one share. Only when a sufficient number of devices (i.e., reaching the threshold) cooperate can a valid signature be generated. This mechanism significantly enhances the security of digital assets, as even if some private key shares are leaked, attackers cannot produce a valid signature. Moreover, threshold signatures prevent single points of failure, ensuring the system’s robustness and continuity. Thus, threshold signatures offer an efficient and secure solution for distributed digital asset management.

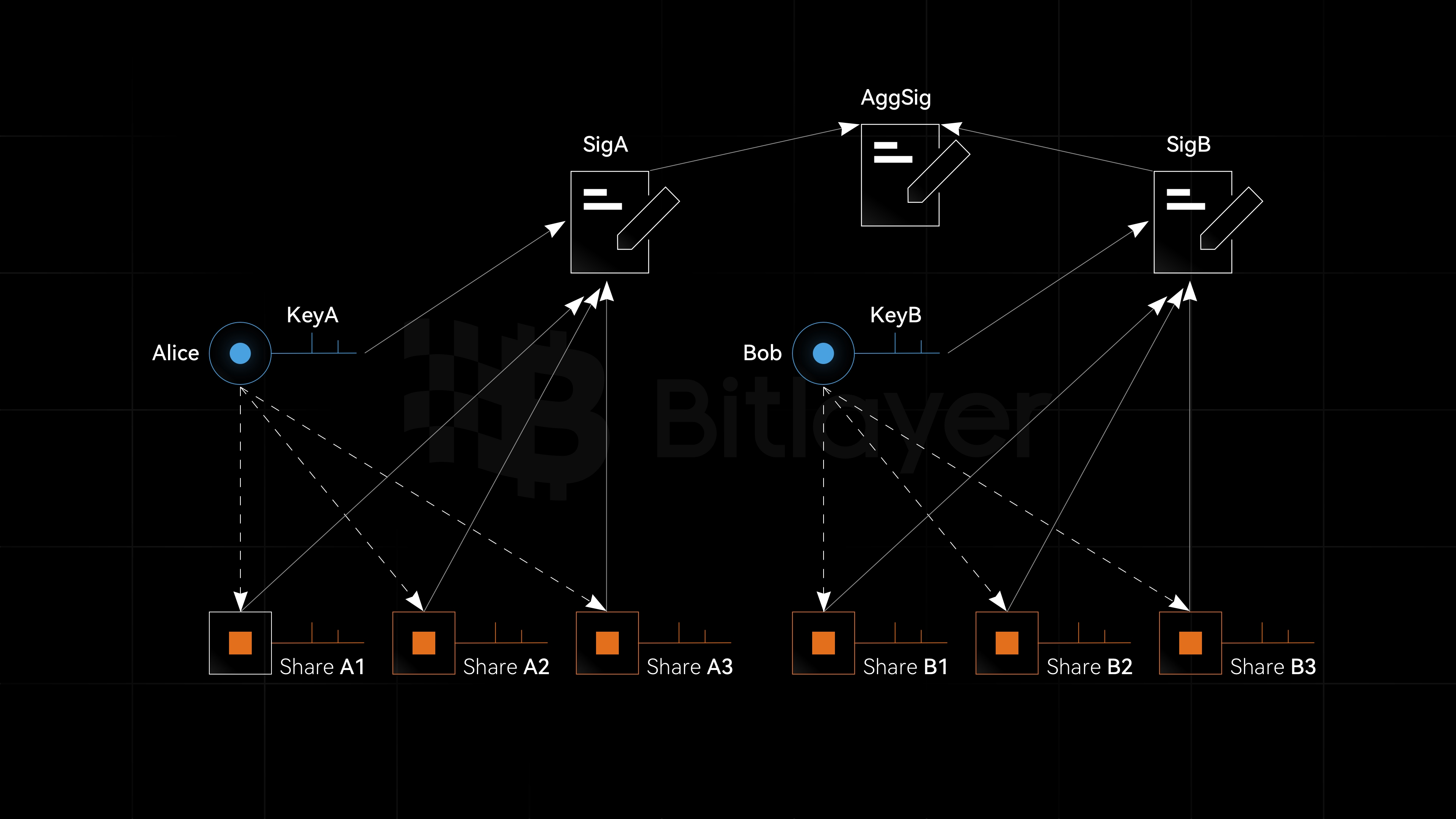

When Alice and Bob both use threshold signatures to manage their respective digital assets and need to apply aggregate signatures (MuSig2) for multi-signature transactions, such as the aforementioned inscriptions, Bitcoin staking, and BitVM co-signing, it is necessary to combine aggregate signatures with threshold signatures to achieve multiple benefits.

As shown in Figure 5, when Alice and Bob use threshold signatures for digital asset custody, the complete private keys KeyA and KeyB do not appear. Instead, their corresponding private key shares, (ShareA1, ShareA2, ShareA3) and (ShareB1, ShareB2, ShareB3), are used. Based on these private key shares, threshold signatures are executed, generating signatures SigA and SigB, respectively. Then, SigA and SigB are aggregated to produce the aggregate signature AggSig. Throughout this process, the complete private keys KeyA and KeyB do not appear. This approach couples threshold signatures with aggregate signatures, thereby meeting multiple application requirements simultaneously.