Adaptor Signatures and Its Application to Cross-Chain Atomic Swaps

1. Introduction

With the rapid development of Bitcoin Layer2 scaling solutions, the frequency of cross-chain asset transfers between Bitcoin and its corresponding Layer2 networks has significantly increased. This trend is driven by the enhanced scalability, lower transaction fees, and high throughput provided by Layer2 technologies such as Bitlayer. These advancements facilitate more efficient and cost-effective transactions, thereby promoting the broader adoption and integration of Bitcoin in various applications. Consequently, the interoperability between Bitcoin and Layer2 networks is becoming a critical component of the cryptocurrency ecosystem, driving innovation and offering users more diverse and robust financial tools.

As shown in Table 1, there are three typical solutions for cross-chain transactions between Bitcoin and Layer2: centralized cross-chain transactions, the BitVM cross-chain bridge, and cross-chain atomic swaps. These technologies differ in terms of trust assumptions, security, convenience, and transaction denominations, catering to different application needs.

| Schemes | Bitcoin side | Layer2 side | Counterparty Restriction | Trust Assumption | Privacy | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Centralized Cross-Chain Transactions | User/ Counterparty 1 transaction | Counterparty/ User 1 transaction | Centralized | 1-of-1 | No, not resistant to censorship | Single point of failure risk |

| BitVM Cross-Chain Bridge | Operator advances 1 transaction; Reimbursement for at least 2 transactions | User 1 transaction | Permissioned. Operator needs to participate in peg-in pre-signing. | 1-of-N | No, not resistant to censorship | If reimbursement is challenged, more L1 transactions are required. |

| Cross-Chain Atomic Swaps | User 1 transaction; Counterparty 1 transaction | User 1 transaction; Counterparty 1 transaction | Permissionless | Trustless | Yes, censorship-resistant | Anyone can participate at any time |

Centralized Cross-Chain Transactions: In this method, users first pay Bitcoin to a centralized entity (such as a project party or exchange), which then pays an equivalent amount of assets on the Layer2 network to the user’s specified address, completing the cross-chain asset transfer. The advantage of this technology lies in its speed and the relative ease of matching transactions, as the centralized entity can quickly confirm and process transactions. However, the security of this method is entirely dependent on the reliability and reputation of the centralized entity. If the centralized entity encounters technical failures, malicious attacks, or defaults, the user’s funds are at high risk. Additionally, centralized cross-chain transactions may leak user privacy, requiring careful consideration when choosing this method. Therefore, despite its convenience and efficiency, the main challenges of centralized cross-chain transactions are security and trust.

BitVM Cross-Chain Bridge: This technology is relatively complex. In the Peg-in phase, users pay Bitcoin to a multi-signature address controlled by the BitVM alliance, locking the Bitcoin. Corresponding tokens are minted on the Layer2 network, which are then used for Layer2 transactions and applications. When users burn the Layer2 tokens, it is paid by the Operator. The Operator then reimburses the corresponding amount of Bitcoins from the multi-signage pool controlled by the BitVM consortium. To prevent malicious behavior by the Operator, an optimistic challenge mechanism is employed, allowing any third party to challenge and thwart malicious reimbursement attempts. This technology is complex due to the introduction of the optimistic challenge mechanism, which involves numerous challenge and response transactions, resulting in high transaction fees. Therefore, the BitVM cross-chain bridge is suitable only for very large transactions, similar to the issuance of U, thus its usage frequency is relatively low.

Cross-Chain Atomic Swaps: An atomic swap is a contract that enables decentralized cryptocurrency trading. In this context, “atomic” means that a change in the ownership of one asset implies a change in the ownership of another asset. The concept was first proposed by TierNolan on the Bitcointalk forum in 2013. For four years, atomic swaps remained theoretical. It wasn’t until 2017 that Decred and Litecoin became the first blockchain systems to complete an atomic swap. Atomic swaps must involve two parties, and no third party can interrupt or interfere with the swapping process. This means that the technology is decentralized, censorship-resistant, provides good privacy protection, and allows for high-frequency cross-chain transactions, making it widely used in decentralized exchanges. Currently, cross-chain atomic swaps require four transactions; some schemes attempt to reduce this number to two transactions, but this increases the real-time online requirements for both parties. Finally, cross-chain atomic swap technology primarily includes hash time-lock contracts (HTLCs) and adaptor signatures.

Cross-Chain Atomic Swaps Based on Hash Time-Lock Contracts (HTLC): The first project to successfully implement a cross-chain atomic swap was Decred, utilizing “hash locks” and “time locks” through on-chain scripts (or smart contracts) to achieve the atomic swap proposed by TierNolan. HTLC allows two users to conduct time-limited cryptocurrency transactions, meaning the recipient must submit cryptographic proof (“secret”) to the contract within a specified time (determined by block number or block height), or the funds will be returned to the sender. If the recipient confirms the payment, the transaction succeeds. Therefore, it requires that the participating blockchains both have “hash lock” and “time lock” functionalities.

Although HTLC atomic swaps are a significant breakthrough in decentralized exchange technology, they have the following issues. These atomic swap transactions and their associated data are conducted on-chain, leading to user privacy leakage. In other words, during each swap, the same hash value appears on both blockchains, only a few blocks apart. This means observers can link the currencies involved in the swap by finding the same hash value in closely-timed blocks (timestamp-wise). When tracking cross-chain currencies, it is easy to determine their origin. While this analysis does not reveal any identity-related data, third parties can easily infer the identities of the participants involved.

Cross-Chain Atomic Swaps Based on Adaptor Signatures: The second type of swap offered by BasicSwap is known as “adaptor signature” atomic swaps, based on a paper published by Monero developer Joël Gugger in 2020 titled “Bitcoin–Monero Cross-chain Atomic Swap”. This paper can be considered an implementation of Lloyd Fournier’s 2019 paper “One-Time Verifiably Encrypted Signatures, A.K.A. Adaptor Signatures”. An adaptor signature is an additional signature that combines with the initial signature to reveal secret data, allowing both parties to simultaneously disclose two parts of the data to each other. It is a key component of the scriptless protocol that makes Monero atomic swaps possible.

Compared to HTLC atomic swaps, atomic swaps based on adaptor signatures have three advantages: First, the adaptor signature swap scheme replaces the on-chain scripts (including time locks and hash locks) that “secret hash” exchanges rely on. In other words, the secret and secret hash in HTLC swaps have no direct correspondence in adaptor signature swaps. Hence, in Bitcoin research, this is referred to as “scriptless scripts”. Additionally, since such scripts are not involved, the on-chain space utilization is reduced, making atomic swaps based on adaptor signatures more lightweight and cost-effective. Finally, while HTLC requires each chain to use the same hash value, the transactions involved in adaptor signature atomic swaps are unlinkable, providing privacy protection.

This paper first introduces the principles of Schnorr/ECDSA adaptor signatures and cross-chain atomic swaps. Then, it analyzes the random number security issues in adaptor signatures and the problems of system and algorithm heterogeneity in cross-chain scenarios, providing solutions. Finally, it extends the application of adaptor signatures to achieve non-interactive digital asset custody.

2. Adaptor Signatures and Its Application to Cross-Chain Atomic Swaps

2.1 Schnorr Adaptor Signatures and Its Application to Cross-Chain Atomic Swaps

Initialization: The group $ \mathbb{G} $ has a generator $ G $ and order $ p $. The collision-resistant hash function $ \mathsf{hash} $ maps arbitrary length data $\{0,1\}^*$ to a random integer in $ \mathbb{Z}_p $.

Key Generation: [Bitcoin Transaction 1] In the Bitcoin system, Alice has 1 BTC. The private key for this asset is $ x \in \mathbb{Z}_p $, and the public key is $ X = x \cdot G $. [Bitlayer Transaction 1] In the Bitlayer system, Bob has 7wU. The private key for this asset is $ y \in \mathbb{Z}_p $, and the public key is $ Y = y \cdot G $.

Pre-signature: Alice selects a random number $ r \leftarrow \mathbb{Z}_p $, inputs the generator $ G $ and the public keys of both parties $ (X, Y) $, and calculates as follows:

\[\begin{aligned} & \hat{R}:=r\cdot G, \\ & R:=\hat{R}+Y, \\ & c:=\mathsf{hash}(R||X||m), \\ & \hat{s}:=r+cx. \\ \end{aligned}\]The pre-signature is $ (\hat{R}, \hat{s}) $. This pre-signature indicates that Alice will pay 1 BTC to Bob’s receiving address.

Pre-sign Verification: Bob receives the pre-signature $ (\hat{R}, \hat{s}) $ and calculates as follows:

\[\begin{aligned} & R:=\hat{R}+Y, \\ & c:=\mathsf{hash}(R||X||m). \\ \end{aligned}\]Bob uses Alice’s public key $ X $ to verify the following equation

\[\hat{R}=\hat{s}\cdot G-c\cdot X.\]The consistency of the verification is as follows:

\[\hat{R}=r\cdot G=(r+cx)\cdot G-c\cdot X=\hat{s}\cdot G-c\cdot X\]Adapt: Bob, based on the pre-signature $ (\hat{R}, \hat{s}) $, inputs his private key and public key $ (y, Y) $ and calculates as follows:

\[\begin{aligned} & R:=\hat{R}+Y, \\ & s:=\hat{s}+y, \\ \end{aligned}\]The signature is $ (R, s) $. Bob broadcasts this signature to the Bitcoin system.

Verification: Bitcoin miners receive the signature $ (R, s) $ and use Alice’s public key $ X $ to verify the following equation as follows:

\[R=s\cdot G-c\cdot X.\]The consistency of the verification is as follows:

\[\begin{aligned} R&=\hat{R}+Y, \\ &=(r+y)\cdot G, \\ &=(r+cx+y)\cdot G-c\cdot X, \\ &=(\hat{s}+y)\cdot G-c\cdot X, \\ &=s\cdot G-c\cdot X \\ \end{aligned}\]Thus, Bob receives 1 BTC from Alice in the Bitcoin system [Bitcoin Transaction 2].

Secret Extraction: Alice calculates the secret $ y $ from the pre-signature $ (\hat{R}, \hat{s}) $ and the signature $ (R, s) $

\[y:=s-\hat{s}.\]Alice uses this secret $ y $ to generate a signature and broadcast it to the Bitlayer system to extract the 7wU from the address $ Y $ [Bitlayer Transaction 2].

2.2 ECDSA Adaptor Signatures and Its Application to Cross-Chain Atomic Swaps

Initialization and key generation are omitted.

Pre-signature: Alice selects a random number $ r \leftarrow \mathbb{Z}_p $, inputs the generator $ G $ and her public key $ Y $, and calculates as follows:

\[\begin{aligned} & \hat{R}:=r\cdot G, \\ & R:=r\cdot Y, \\ & \pi :=\mathsf{zk}\{r|\hat{R}=r\cdot G,R=r\cdot Y\}, \\ & R_x:=f(R) ,\\ & \hat{s}:=r^{-1}(\mathsf{hash}(m)+R_x x). \\ \end{aligned}\]The pre-signature is $ (R, \hat{R}, \hat{s}, \pi) $, where $ f(R) $ refers to the x-coordinate $ R_x $ of $ R $. The pre-signature indicates that Alice will pay 1 BTC to Bob.

Pre-sign Verification: Bob receives the pre-signature $ (R, \hat{R}, \hat{s}, \pi) $, verifies the zero-knowledge, calculates $ R_x = f(R) $, and uses Alice’s public key $ X $ to verify the pre-signature

\[\begin{aligned} & \mathsf{Verify}\left( \pi ,(G,\hat{R})(R,Y) \right)=1, \\ & \hat{s}\cdot \hat{R}=\mathsf{hash}(m)\cdot G+R_x\cdot X. \\ \end{aligned}\]The consistency of the verification is as follows:

\[\hat{s}\cdot \hat{R}=r^{-1}(\mathsf{hash}(m)+R_xx)\cdot \hat{R}=\mathsf{hash}(m)\cdot G+R_x\cdot X\]Adapt: Bob, based on the pre-signature $ (R, \hat{R}, \hat{s}, \pi) $, inputs his private key $ y $, and calculates as follows:

\[s:=\hat{s}y^{-1},\]The signature is $ (R_x, s) $. Bob broadcasts this signature to the Bitcoin system.

Verification: Bitcoin miners receive the signature $ (R_x, s) $ and use Alice’s public key $ X $ to verify as follows:

\[R_x=f\left( s^{-1}(\mathsf{hash}(m)\cdot G+R_x\cdot X) \right).\]The consistency of the verification is as follows:

\[\begin{aligned} & R_x=f(R) \\ & =f(r\cdot Y) \\ & =f(ry\cdot G) \\ & =f(r(\mathsf{hash}(m)+R_x x)^{-1}y(\mathsf{hash}(m)+R_xx)\cdot G) \\ & =f\left( {s^{-1}}(\mathsf{hash}(m)\cdot G+R_x\cdot X) \right) \\ \end{aligned}\]Thus, Bob receives 1 BTC from Alice in the Bitcoin system [Bitcoin Transaction 2].

Secret Extraction: Alice, based on the pre-signature $ (R, \hat{R}, \hat{s}, \pi) $ and the signature $ (R_x, s) $, calculates as follows:

\[y':=s^{-1}\hat{s}.\]If $ y’ \cdot G = Y $, then $ y = y’ $; if $ -y’ \cdot G = Y $, then $ y = -y’ $. Alice uses the secret $ y $ to generate a signature and broadcasts it to the Bitlayer system to extract the 7wU from the address $ Y $ [Bitlayer Transaction 2].

2.2.1 Zero-knowledge Proof $\mathsf{zk}\{r|\hat{R}=r\cdot G,R=r\cdot Y\}$

Commitment: The prover selects a random number $ v \leftarrow \mathbb{Z}_p $ and calculates the commitment

\[\hat{V}:=v\cdot G,~~V:=v\cdot Y.\]Challenge: The prover calculates the challenge

\[c:=\mathsf{hash}(\hat{R},G,R,Y,\hat{V},V).\]Response: The prover calculates the response.

\[z:=v+cr.\]Proof Transmission: The proof $ \pi = (\hat{R}, G, R, Y, \hat{V}, V, z) $ is sent.

Verification: The verifier calculates the challenge $ c := \mathsf{hash}(\hat{R}, G, R, Y, \hat{V}, V) $ and then verifies the following two equations

\[\begin{aligned} & z\cdot G=\hat{V}+c\cdot \hat{R}, \\ & z\cdot Y=V+c\cdot R.\\ \end{aligned}\]The consistency of the verification is as follows:

\[\begin{aligned} & z\cdot G=(v+cr)\cdot G=\hat{V}+c\cdot \hat{R} \\ & z\cdot Y=(v+cr)\cdot Y=V+c\cdot R \\ \end{aligned}\]3. Security Problems and Solutions

3.1 Random Number Problems and Solutions

3.1.1 Random Number Leak Problems

In Schnorr/ECDSA adaptor signatures, the pre-signature commits to a random number $ r $ such that $ \hat{R} = r \cdot G $. Additionally, in zero-knowledge proofs, the random number $ v $ is committed as $ \hat{V} = v \cdot G $ and $ V = v \cdot Y $. If the random number is leaked, it results in the leakage of the private key.

Specifically, in the Schnorr protocol, if the random number $ r $ is leaked, the private key $ x $ can be calculated using the equation

\[\hat{s}=r+cx\]Similarly, in the ECDSA protocol, if the random number $ r $ is leaked, the private key $ x $ can be calculated using the equation

\[\hat{s}=r^{-1}(\mathsf{hash}(m)+R_x x)\]Finally, in the zero-knowledge proof protocol, if the random number $ v $ is leaked, the random number $ r $ can be calculated using the equation

\[z:=v+cr\]which then allows for the calculation of the private key $ x $ from $ r $. Therefore, random numbers must be deleted immediately after use.

3.1.2 Random Number Reuse Problems

For any two cross-chain transactions, if the adaptor signature protocol uses the same random number, it will lead to private key leakage. Specifically, in the Schnorr protocol, if the same random number $ r $ is used, the following system of equations contains only $ r $ and $ x $ as unknowns:

\[\left\{ \begin{aligned} & \hat{s}_1=r+c_1x, \\ & \hat{s}_2=r+c_2x. \\ \end{aligned} \right.\]Thus, the system can be solved to obtain the private key $ x $. Similarly, in the ECDSA adaptor signature protocol, if the same random number $ r $ is used, the following system of equations contains only $ r $ and $ x $ as unknowns:

\[\left\{ \begin{aligned} & \hat{s}_1=r^{-1}(\mathsf{hash}(m_1)+R_x x), \\ & \hat{s}_2=r^{-1}(\mathsf{hash}(m_2)+R_x x). \\ \end{aligned} \right.\]Thus, the system can be solved to obtain the private key $ x $. Finally, in the zero-knowledge proof protocol, if the same random number $ v $ is used, the following system of equations contains only $ v $ and $ r $ as unknowns:

\[\left\{ \begin{aligned} & z_1=v+c_1r, \\ & z_2=v+c_2r. \\ \end{aligned} \right.\]Thus, the system can be solved to obtain the random number $ r $, which then allows for solving the system to obtain the private key $ x $. By extension, different users using the same random number will also leak their private keys.

In other words, two users using the same random number can solve the system of equations to obtain each other’s private key. Therefore, RFC 6979 should be used to address the issue of random number reuse.

3.1.3 Solutions: RFC 6979

RFC 6979 specifies a method for generating deterministic digital signatures using DSA and ECDSA, addressing the security issues related to generating random values $ k $. Traditional DSA and ECDSA signatures rely on a randomly generated $ k $ for each signing operation. If this random number is reused or improperly generated, it endangers the security of the private key. RFC 6979 eliminates the need for generating a random number by deterministically deriving $ k $ from the private key and the message to be signed. This ensures that the signature is always the same when signing the same message with the same private key, enhancing reproducibility and predictability. Specifically, the deterministic $ k $ is generated by HMAC. This process involves hashing the private key, message, and a counter using a hash function (such as $\mathsf{SHA256}$),

\[k=\mathsf{SHA256}(sk, msg, counter).\]For simplicity, the equation only shows hashing the private key $ sk$, message $ msg $, and counter $counter$; the actual RFC 6979 process involves more hashing steps. This ensures that $ k $ is unique for each message and reproducible with the same inputs, reducing the risk of private key exposure associated with weak or compromised random number generators. Consequently, RFC 6979 provides a robust framework for deterministic digital signatures using DSA and ECDSA, addressing significant security issues related to random number generation and enhancing the reliability and predictability of digital signatures. This makes it a valuable standard for applications requiring high security and strict operational requirements. Since Schnorr/ECDSA signatures have random number flaws, they need to use RFC 6979 for protection. Therefore, adaptor signatures based on Schnorr/ECDSA also have these issues and require RFC 6979 to resolve them.

3.2 Cross-chain Scenario Problems and Solutions

3.2.1 Issues and Solutions for Heterogeneous UTXO and Account Model Systems

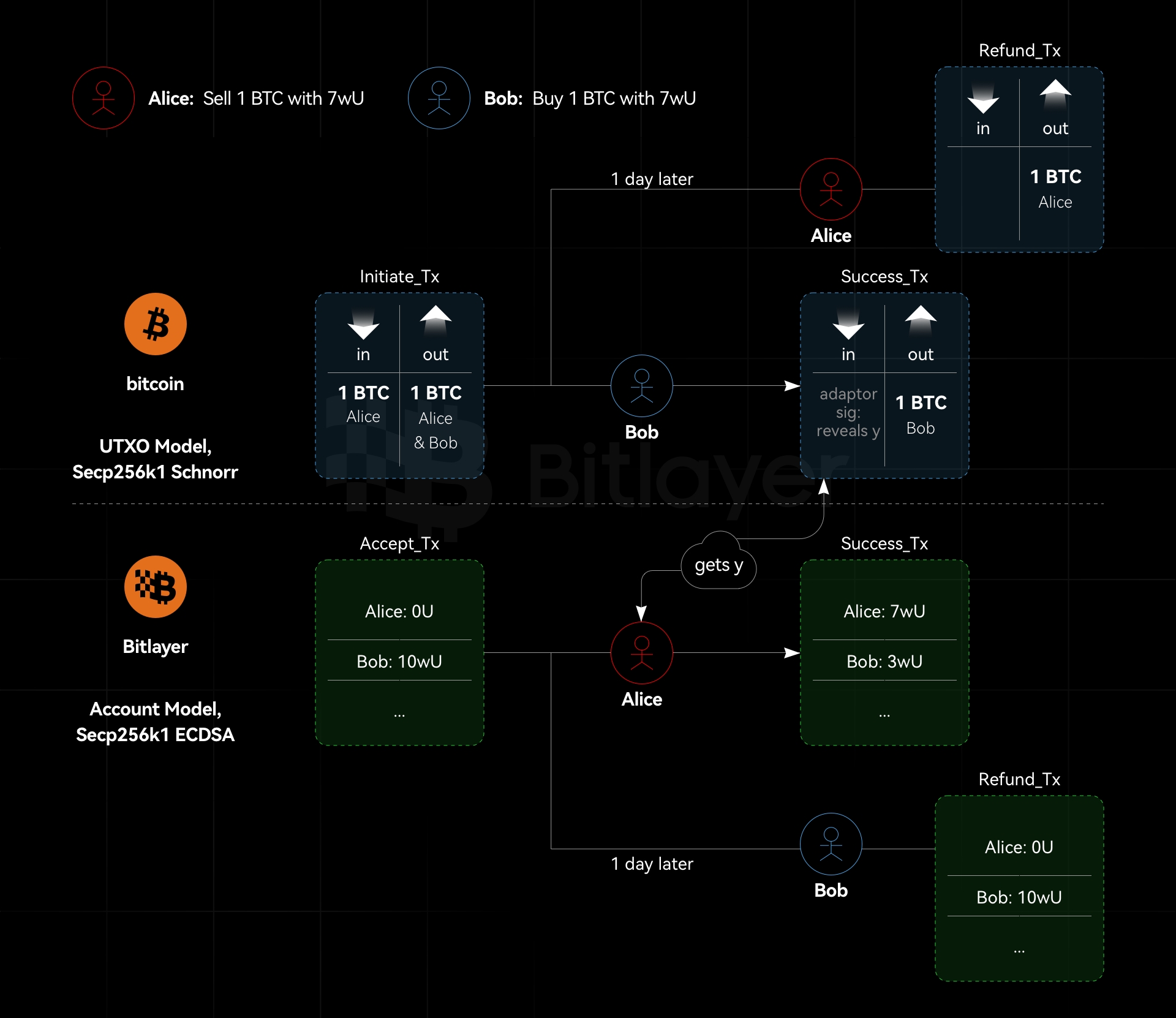

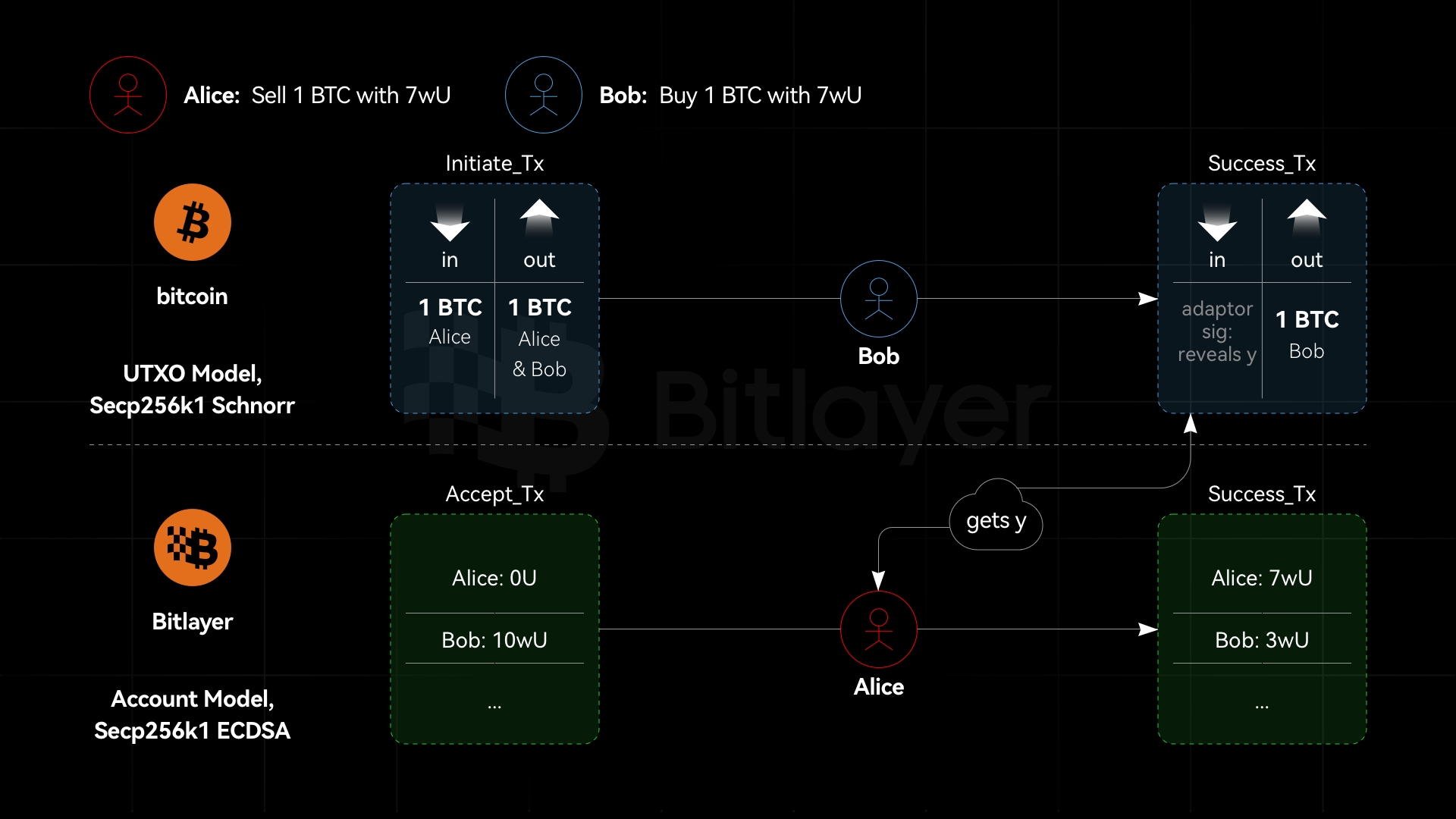

As shown in Figure 1, Bitcoin uses the UTXO model and implements native ECDSA signatures based on the Secp256k1 curve. Bitlayer is an EMV-compatible Bitcoin L2 chain, also using the Secp256k1 curve and supporting native ECDSA signatures. Adaptor signatures achieve the required logic for BTC swaps, while the corresponding Bitlayer swaps are supported by the robust capabilities of Ethereum smart contracts.

Cross-chain atomic swaps based on adaptor signatures, or at least semi-scriptless adaptor signature schemes designed for the ECDSA curve, are incompatible with Ethereum. This is because Ethereum uses the account model, not the UTXO model. Specifically, in adaptor signature-based atomic swaps, refund transactions must be pre-signed. However, in the Ethereum system, transactions cannot be pre-signed without knowing the nonce. Therefore, one party can send a transaction between the pre-signature and the transaction execution, invalidating the pre-signed transaction (because the nonce has been used and cannot be reused).

From a privacy perspective, this means that Bitlayer swaps offer better anonymity than HTLC (both parties can locate the contract). However, since one party needs a public contract, Bitlayer swaps have lower anonymity than adaptor signatures. On the non-contract side, swap transactions look like any other transaction. However, on the EVM contract side, the transaction indicates an asset swap. Although one party has a public contract, it is impossible to trace it back to the other chain using even sophisticated chain analysis tools.

Bitlayer currently supports native ECDSA signatures and can also verify Schnorr signatures through smart contracts. If using native Bitlayer transactions, it is not possible to pre-sign the refund transaction in atomic swaps; thus, Bitlayer smart contract transactions must be used to achieve atomic swaps. However, this process sacrifices privacy, meaning that transactions involved in atomic swaps within the Bitlayer system are traceable but cannot be traced back to the transactions in the BTC system. On the Bitlayer side, a Dapp similar to Tornado Cash can be designed to provide privacy services for the Bitlayer side of BTC and Bitlayer atomic swaps.

3.2.2 Same Curve, Different Algorithms, Adaptor Signatures are Secure

As shown in Figure 2, suppose Bitcoin and Bitlayer both use the Secp256k1 curve, with Bitcoin using Schnorr signatures and Bitlayer using ECDSA. In this case, adaptor signatures based on Schnorr and ECDSA are provably secure. Suppose a simulator $\mathcal{S}$ can break ECDSA given ECDSA and Schnorr signature oracles; it can also break ECDSA with only the ECDSA signature oracle. However, ECDSA is secure. Similarly, suppose a simulator $\mathcal{S}$ can break Schnorr signatures given ECDSA and Schnorr signature oracles; it can also break Schnorr signatures with only the ECDSA signature oracle. However, the Schnorr signature is secure. Therefore, in cross-chain scenarios where adaptor signatures use the same curve but different signature algorithms, they are secure. In other words, adaptor signatures allow one side to use ECDSA and the other side to use Schnorr signatures.

3.2.3 Different Curves, Adaptor Signatures are Not Secure

Suppose Bitcoin uses the Secp256k1 curve with ECDSA signatures, and Bitlayer uses the ed25519 curve with Schnorr signatures. In this case, adaptor signatures cannot be used due to the different curves, which result in different orders of the elliptic curve groups and different modulus coefficients. When Bob adapts $y$ into the ECDSA signature in the Bitcoin system, he calculates $s:=\hat{s}+y$. At this point, the value space of $y$ is the scalar space of the Secp256k1 elliptic curve group. Subsequently, Alice needs to use $y$ to perform Schnorr signatures on the ed25519 elliptic curve group. However, the cofactor of the ed25519 curve is 8, and its modulus coefficient differs from the Secp256k1 elliptic curve group. Therefore, using $y$ to perform Schnorr signatures on the ed25519 curve is not secure.

4. Applications in Digital Asset Custody

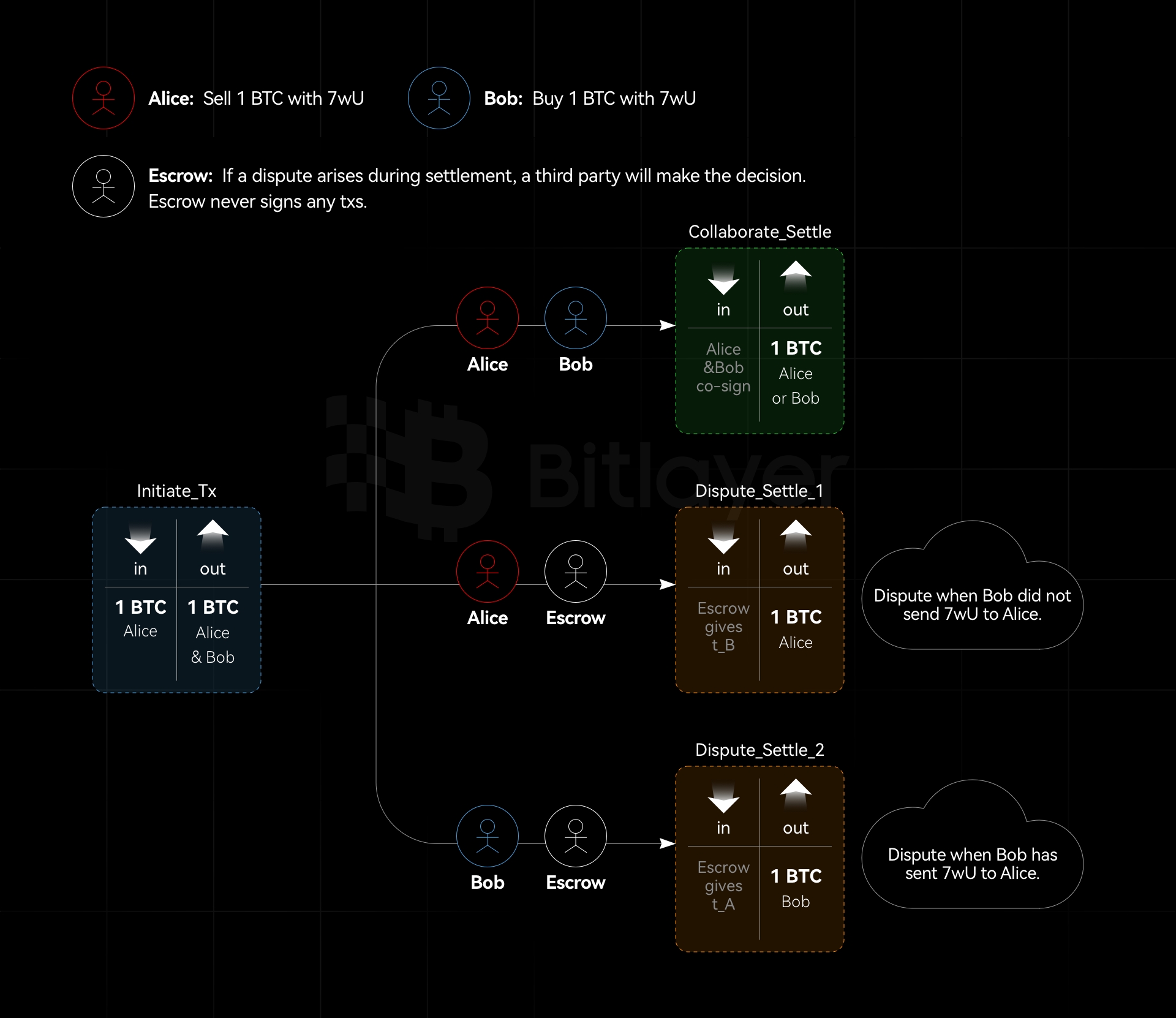

Digital asset custody involves three participants: a buyer Alice, a seller Bob, and a custodian. Adaptor signatures enable non-interactive threshold digital asset custody, instantiating a subset of the threshold spending strategy without interaction. This subset consists of two types of participants: those who participate in initialization and those who do not, the latter being the custodian. The custodian cannot sign any transaction but can only release the secret to one of the supported parties.

On one hand, the custodian can only choose from a few fixed settlement transactions and cannot sign new transactions with any of the other participants. Thus, this secret release mechanism makes the non-interactive threshold custody less flexible than threshold Schnorr signatures. On the other hand, a 2-of-3 spending strategy can be set up using threshold Schnorr signatures. However, the threshold Schnorr signature protocol requires all three parties to run a decentralized key generation protocol. Therefore, the asset custody protocol based on adaptor signatures has the advantage of being non-interactive.

4.1 Non-interactive Asset Custody Based on Adaptor Signatures

As shown in Figure 3, Alice and Bob want to create a 2-of-3 transaction output with a hidden strategy, involving a custodian. Depending on the condition $ c $, either Alice or Bob can spend the transaction output. If a dispute arises between Alice and Bob, the custodian (with public key $ E $ and private key $ e $) decides whether Alice or Bob gets the asset.

-

Create an unsigned funding transaction that sends BTC to a 2-of-2 MuSig output between Alice and Bob.

-

Alice selects a random value $ t_A $ and sends Bob a Schnorr pre-signature $(\hat{R}_A, \hat{s}_A)$ with the adaptor $ t_A \cdot G $. This transaction sends the funding output to Bob. Alice also sends Bob a ciphertext containing the secret $ t_A $ and the adjusted custodian public key $ E_c = E + \mathsf{hash}(E, c)G $ in a verifiable encryption $ C = \mathsf{Enc}(E_c, t_A) $. During this process, Bob cannot spend the funding output because adding his signature does not satisfy the 2-of-2 MuSig. Only if Bob knows $ t_A $ (which the custodian can provide), or if Alice sends a complete signature, can Bob spend the funding output.

-

Correspondingly, Bob repeats step (2) with his adaptor secret $ t_B $, signing a transaction that sends the funding output to Alice.

-

Both Alice and Bob verify the validity of the received ciphertexts, ensuring they are encryptions of secrets to $ E_c $. They then sign and broadcast the funding transaction. Verifiable encryption allows the setup phase without custodian involvement and does not require making the contract $ c $ public to custodian.

-

In case of a dispute, Alice and Bob can send the ciphertexts and condition $ c $ to the custodian, who will make a decision based on the actual situation and uses the adjusted private key $ e + \mathsf{hash}(E, c) $ to decrypt $ t_A / t_B $ for Bob/Alice accordingly.

If no dispute arises, Alice and Bob can spend the 2-of-2 MuSig output as they wish. If there is a dispute, either party can contact the custodian and request the adaptor secret $ t_A $ or $ t_B $. With the custodian’s help, one party can complete the adaptor signature and broadcast the settlement transaction.

4.2 Verifiable Encryption

The classic verifiable encryption scheme based on the discrete logarithm (Practical Verifiable Encryption and Decryption of Discrete Logarithms) cannot be used for Secp256k1 adaptors because it only supports verification in specially structured groups. Now, there are two promising methods for performing verifiable encryption based on the discrete logarithm over Secp256k1: Purify and Juggling.

Purify was initially proposed to create a MuSig protocol with deterministic nonces (DN), requiring each signer to use zero-knowledge proofs to show that their nonce is the result of correctly applying a pseudo-random function (PRF) to the public key and message. The Purify PRF can be efficiently implemented within the arithmetic circuits of the Bulletproofs zero-knowledge protocol, facilitating the creation of a verifiable encryption scheme for discrete logarithms on Secp256k1. In other words, verifiable encryption is achieved using zkSnark.

Juggling encryption involves four steps: (1) split the discrete logarithm $ x $ into several segments of length $ l $, $ x_k $, such that $ x = \sum_k 2^{(k-1)l} x_k $; (2) use the public key $ Y $ to ElGamal encrypt the segments $ x_k \cdot G $, yielding $ { D_k, E_k} = { x_k \cdot G + r_k \cdot Y, r_k \cdot G } $; (3) create range proofs for each $ x_k \cdot G $, demonstrating that $ D_k $ is a Pedersen commitment to $ x_k \cdot G + r_k \cdot Y $ and that its value is less than $ 2^l $; (4) use a sigma protocol to prove that $ { \sum D_k, \sum E_k } $ correctly encrypts $ x_k \cdot G $. During decryption, each $ { D_k, E_k } $ is decrypted to $ x_k \cdot G $, and $ x_k $ is found by exhaustive search within the range $[0, 2^l)$.

Purify requires executing a PRF within Bulletproofs, which is relatively complex, while Juggling is theoretically simpler. Additionally, the differences in proof size, proving time, and verification time between the two methods are minimal.

5. Conclusion

This article provides a detailed description of the principles behind Schnorr/ECDSA adaptor signatures and cross-chain atomic swaps. It deeply analyzes the issues of random number leakage and reuse in adaptor signatures and proposes using RFC 6979 to resolve these problems. Furthermore, it examines the cross-chain application scenarios, considering not only the differences between blockchain UTXO models and account models but also whether adaptor signatures support different algorithms and curves. Finally, it extends the application of adaptor signatures to non-interactive digital asset custody and briefly introduces the involved cryptographic primitive—verifiable encryption.

References

1. Gugger J. Bitcoin-monero cross-chain atomic swap[J]. Cryptology ePrint Archive, 2020.

2. Fournier L. One-time verifiably encrypted signatures aka adaptor signatures[J]. 2019, 2019.

3. https://crypto-in-action.github.io/ecdsa-blockchain-dangers/190816-secp256k1-ecdsa-dangers.pdf

4. Pornin T. Deterministic usage of the digital signature algorithm (DSA) and elliptic curve digital signature algorithm ECDSA. 2013.

5. Komlo C, Goldberg I. FROST: flexible round-optimized Schnorr threshold signatures[C]//Selected Areas in Cryptography: 27th International Conference, Halifax, NS, Canada (Virtual Event), October 21-23, 2020, Revised Selected Papers 27. Springer International Publishing, 2021: 34-65.

6. https://github.com/BlockstreamResearch/scriptless-scripts/blob/master/md/NITE.md

7. https://particl.news/the-dex-revolution-basicswap-and-private-ethereum-swaps/

8. Camenisch J, Shoup V. Practical verifiable encryption and decryption of discrete logarithms[C]//Annual International Cryptology Conference. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2003: 126-144.

9. Nick J, Ruffing T, Seurin Y, et al. MuSig-DN: Schnorr multi-signatures with verifiably deterministic nonces[C] //Proceedings of the 2020 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security. 2020: 1717-1731.

10. Shlomovits O, Leiba O. Jugglingswap: scriptless atomic cross-chain swaps[J]. arXiv preprint arXiv:2007.14423, 2020.